Our house in Niterói–Mirante de São Francisco

Jean had the address. Marcelo had the address. We had liquor in the car in addition to TWO tiny cans of tomato juice and the snacks Pettus had bought. I had nothing to worry about, as usual. I couldn’t logisticize my way out of a paper bag, so having Jean to plan everything is a blissful thing, indeed.

Marcelo piloted us almost surreptitiously through many of the same back streets as before, and seemed to know the area pretty well. We later found out that he was indeed from Niterói, but at this moment, we were just amazed at his skills. He picked up his radio/cell phone and began another mysterious conversation with his “contact” on the other end. Given all the fast, slidey, zzhh-zzhh talk going on sotto voce between them, I couldn’t tell if he was looking for the house, or arranging to have us kidnapped. It would be just our luck to get THAT driver.

We finally came out at a large four-lane boulevard with a nice planted median broken by turnarounds all the way up and down the street. The side opposite us was striped with roads all going up the mountain to different subdivisions, apparently. Marcelo took a right, got in the left lane, turned through the median and got on the other side in the right lane. We saw a gated street on the right, and he turned in. Marcelo rolled down the window and began a quick conversation with the “guard,” a guy in street clothes wearing a windbreaker and managing to smoke a cigarette under the hood without getting it wet. Looked qualified to me. He shook his head at Marcelo, his ashes flying in a semicircle, and pointed down the street. I heard “dois,” I think.

Marcelo gave his first thumbs-up of our visit, to my secret delight. He zoomed off down the street (as fast as one can “zoom” with God-knows-how-many pounds of humanoids AND 3 tons of luggage) and began to turn in the next street. It was also gated, and there was also a guard, but he didn’t even get up from his lawn chair. The gate opened obediently and we pulled right through. Marcelo rolled the window down and did the short directional interrogation. The guy shook his head and pointed UP the street. Great. This gave me a second to reflect on the security industry in Brazil. Obviously thriving. No office required. No investment. Plenty o’ business. Only requirements would be an ability to appear whoop-ass, and surface trustworthiness. And in many cases, I suspect the mere presence of a guard is just enough deterrent for would-be criminals.

Marcelo pulled out, went through the median, and turned back in the other direction. He made another left turn through the third median, just in time to realize that the street we wanted was 50 feet BEHIND us. Sheiss! Back to the next turnaround, down the requisite number of blocks, and then a turn onto our street. With no gate. And no guard. Hmmm. I was immediately assuaged when I saw the initial houses on the street–cool modernist architecture in the Brazilian style–the delightful marriage of clean lines and Mediterranean accents. Me likee!!

The road was steep immediately, and we began to slightly rattle up the rough surface. Every turn was a hairpin as we climbed steadily. At the second curve, I saw what appeared to be a concrete favela on the right, and casually said, “There it is,” all the while waiting on somebody to refute the remark. Marcelo just looked at me with no expression. I began to wonder if that appeared to be an elitist asshole American remark, though meant in jest.

We continued up and around, trying to find our address. It was then that we discovered that the houses were numbered randomly. Odd and even numbers appeared on both sides of the street, and we passed 2230, 512, 440, 132, 3235, and never did find our number. Another Brazilian oddity? I didn’t think so. Marcelo seemed as baffled as we did. He got on the radio again to chat with “control.”

“Okay,” he said, and immediately took a right turn onto a small street that was at an 89 degree angle up the hill. The valves clattered, the car stuttered, and I turned to half-jokingly ask, “Do we need to get out?”

“No,” he said calmly, as he rolled back down the street to get a running start. We all began to cheer him and the car at the herculean effort. It took the hill with the surety of a mountain goat. At the top of THAT road, he took a left and began going around a curve surrounded by rock walls on both sides. The houses were all behind wooden or iron gates, which came right up to the street. There were very demure little V-shaped spikes on all the walls, rooflines, and anywhere else a ne’er-do-well may put his Havaianas. So much classier than good-ole razor wire, which was also in existence, but not so blatantly. “There it is,” Marcelo said, and we saw a little guard shack with a windbreaker-clad guy smoking inside. It was between two houses, ours being the one on the right.

The gate had a digital keypad on the outside that worked in conjunction with the key. After 8 or ten tries, with Marcelo’s help we got in. Immediately inside was a small courtyard, partially covered by the house roof. The water was sheeting off the barrel tiles onto the concrete, and I trod gently in my Crocs, fearing a slip. Meanwhile, we had been met by a young black Brazilian with a tall, Frankensteinish head, wearing black nerd glasses with white adhesive tape on one earpiece. This was Robson (pronouned “Hobson.” Carol told me that she felt sure that his name was “Robson,” a very common Brazilian name, and that, of course, it would be pronounced “Hobson.”). With him were a couple of other guys and two women. They immediately began to bring in the luggage, Robson orchestrating the whole event in Portuguese, speaking only rarely to us in obsequious English. This was always accompanied by an unnerving half-bow, both hands in prayer position. I really don’t want anyone bowing to me. Oh, all right. Maybe Jean. Hahahahahahaaaahhaaaaaaaa!!!!!

Jean had thought it prudent to line up Marcelo for the next day to take us to Copacabana to get our Carnaval tickets from the broker. “They told us we had access to a driver the whole time we’re here,” she said in her international tone. “Are you our driver?”

“If you want me to be, yes,” Marcelo replied. Did I detect a slight gleam?

“We do!” we all shouted. “Can we just arrange with you?” Jean asked.

“Yes, but you must call and book me,” he said.

“Okay, we’ll do that, but we’ll tell you first. Can you take us to Rio tomorrow?”

“Yes,” he said. “You will call Sylvia.”

We waved goodbye to Marcelo as he did a beautiful 3-point turn in the narrow, cobbled street, gave the secret sign to the guard, and disappeared around the corner. While Robson and his minions distributed the luggage, we walked into our (gulp!) un-airconditioned-except-for-bedrooms house. There was a large fan in two corners of the huge room. I set them to work immediately before anything else.

Of course the Kennemers didn’t care about the lack of air. They can live comfortably in any environment. Their home in Birmingham (designed by my father!) is a gorgeous, what they now call “mid-century” house on the crest of Shades Mountain. It was without air conditioning when they bought it 28 years ago, and they kept it that way until very recently, being perfectly happy with the breezes off the mountain that rushed through the breezeway. Pettus said she got hot a few times in the summer, but most of the time was fine. They had an air conditioner in their bedroom that made Robo cold. Pettus would describe lying in bed with no covers burning up while Robo snored under three blankets.

Jean and I, meanwhile, like our air conditioner set at “meat locker” 24/7.

We went out onto the back porch to look at our stellar view of the bay: Sugarloaf, and the Christ statue, in addition to several forts, sailboats, and even a McDonald’s. What?

Wow! Idyllic.

Wow! Idyllic.

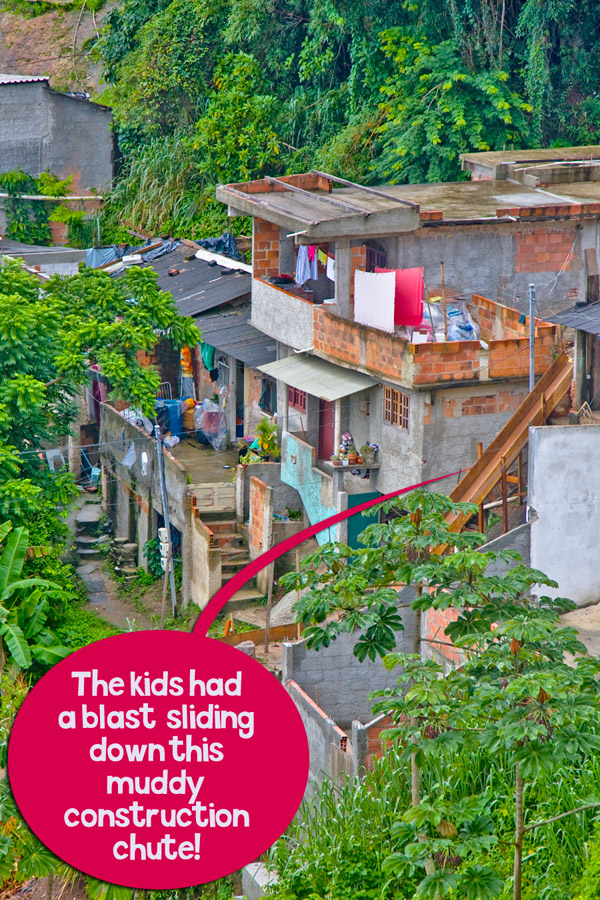

We then looked to the right and down one tier at some of our neighbors. The dichotomy of lifestyle quality in Brazil in such close proximity slapped me in the face. I don’t know if this was an abandoned house under construction, as the one we saw earlier may have been, because both houses had construction chutes. Given the fact that our neighbors’ construction chute doubled as a mudslide for the kids, it was probably abandoned construction.

Once back inside, we saw that Robson and crew had taken the luggage down one floor to the bedrooms. There were three on the floor, the master bedroom suite featuring all the steam/jacuzzi stuff of hedonist dreams. We gave that bedroom to Pettus and Robo and took the one nearest the stairs. It was cozy goodness. There was a balcony that ran the length of the house on this floor as well, but we never went out on it, of course. It was the kind of thing that a vacationer would use only after having exhausted all other Rio entertainment. We didn’t have that kind of time.

Once back inside, we saw that Robson and crew had taken the luggage down one floor to the bedrooms. There were three on the floor, the master bedroom suite featuring all the steam/jacuzzi stuff of hedonist dreams. We gave that bedroom to Pettus and Robo and took the one nearest the stairs. It was cozy goodness. There was a balcony that ran the length of the house on this floor as well, but we never went out on it, of course. It was the kind of thing that a vacationer would use only after having exhausted all other Rio entertainment. We didn’t have that kind of time.

By this time, Sylvia, the mysterious concierge from the other end of Jean’s phone calls, had appeared upstairs with Maria, our cook. We headed up to meet them. Maria said hardly anything at all. She had an Amazon native look about her, with a body that went from her torso immediately to her head. She was very sweet, but also smashed by submissive body language. I knew I was gonna have to work hard to make her love me.

Sylvia was a dish. She elicited an immediate Roy Orbison growl, which drew a smile, but not a giggle. Sophisticated city girls don’t tumble as quickly as the Bahians? Hmmm. Tough crowd.

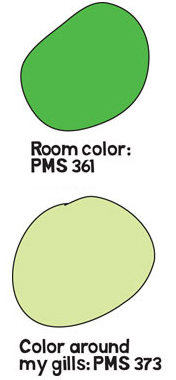

She led us downstairs to the bottom floor for our orientation and our first caipirinhas. The basement area was incredible, painted a gorgeous Pantone 361 green. The stairs ended in a large wet bar with refrigerator and drinking water machine, the bottle hidden by a needlepointed cover that said “Rio Holiday,” bearing a sign that said “WE DRINK BOTTLED WATER HERE.” I gave an involuntary shudder at what was obviously another message from Iemanjá.

She led us downstairs to the bottom floor for our orientation and our first caipirinhas. The basement area was incredible, painted a gorgeous Pantone 361 green. The stairs ended in a large wet bar with refrigerator and drinking water machine, the bottle hidden by a needlepointed cover that said “Rio Holiday,” bearing a sign that said “WE DRINK BOTTLED WATER HERE.” I gave an involuntary shudder at what was obviously another message from Iemanjá.

There was shelf after shelf of gleaming glass topped with all sorts of different liquor for use/purchase. Not a drop of Meyers’s Rum anywhere, but THREE bottles of Bacardi Gold. Sigh. The prices for consume/buy were comparable to what you would have paid at a store. We actually paid a little more for our Bacardi Gold at the bodega than we would have had to pay to have the bottle fall over on the shelf and pour into our mouths.

The bottom floor also had a pool table, a ping pong table, big screen TV, and an elevated bedroom suite in the middle of it all. It opened out onto the patio and pool, replete with barbeque facilities, etc. Just like Cerqueira-la! What a fabulous place.

The two other women were working busily at the bar making our drinks while Sylvia gave us the lowdown on Mirante de São Francicso. Her English was stellar, with an accent like one of the Muldovian princesses on any episode of Mission: Impossible. Woo! The only word that she missed repeatedly was “taxi,” which she pronounced “tax.” It was so charming to hear her tell us we could go down to the restaurants, then call her to get a “tax.” It was then that I felt compelled to ask her the big question:

“Sylvia, can we flush toilet paper here, or do we have to use the garbage cans?” She looked at me with an expression that changed from incredulity to amusement to business in a split second.

“You can use the garbage cans for the toilet paper if you want,” was all she said before moving on to the next feature of the house. In retrospect, maybe she was so flummoxed by the fact that I would not only know about the toilet paper secret, but would ask about it. But I’m sure her mind’s eye was viewing a film that she would rather not see.

By then, our drinks were ready. They were delicious, and we were gonna learn how to do them. That’s what the “unlimited caipirinhas” part of the deal meant. We had access to all the cachaça we wanted, and bowls, baskets and bushels of limes, limes, limes! Yessiree! Get down!

NOT SO FAST, BURFORD.

NOT SO FAST, BURFORD.

I was still a little green around the gills (not quite the Pantone 361, more like a 373), and though I sipped my drink, I didn’t wolf it down the way the REAL Ben Burford would have. The pod person sitting in my place almost hurled as Sylvia mentioned the fact that we could have a chef come over and do us a barbeque if we wanted.

I then realized that I was experiencing anxiety on all fronts. Here’s this huge fantastic house with all this room. Blackledge can’t come. We’ll never use all the space. It’s raining. When will it quit? When will my gullet set me free? How much was this house? Are those people down the hill happy? Will Marcelo remember to get us? You mean you have to come all the way down here for the liquor? When will we use this pool? What about the kids? I wonder if the dogs are all right. What am I gonna do about running out of flash card space? I don’t play pool well. Nor ping pong. What’s this checkers set with shot glasses for pieces on the table? I can’t drink that much. How will we ever take advantage of our free caipirinhas? We’ll never use all this space. Why is there razor wire everywhere? What are we gonna do here? Will it be hard to get places? Will everything be crowded? What about our Carnaval tickets? Did we get ripped off? WHERE THE HELL is CAROL?!

Sylvia was wrapping up her presentation. It was time for me to learn how to make the caipirinhas, which was a great diversion at the time. The two ladies demonstrated the smashing of the limes with the mortar and pestle (wooden), the addition of a couple of spoons of sugar from the covered dish designed to dissuade ants (not), followed by two shots of cachaça, measured with a jigger. The instructor looked at me quizzically to see if I got it? Of course I got it. As she repeated the directions for closure, ending with “and then two of the cachaça,” I countered with “o mais!” Both ladies giggled. Ahhhh. Still golden, though still jittery.

Sylvia’s job entailed anything we wanted her to do. Well, you know, not ANYTHING, but really, anything. She would even order pizza for us, get the “tax” to bring it to us, and tell the driver how to get here and everything. That sounded good to us. (Or as good as anything could sound to me). We wanted to hang around on the main level and learn how to work the TV, internet, and free long distance.

Ahh, yes. The FREE long distance. It became my three companions’ major obsession getting it to work. They kept talking in carrier-ese, and saying stuff about Seattle that I didn’t understand. Jean talked to a couple of people, Sylvia first, and I believe it was fixed in a couple of days. Who knows? I didn’t want to call anybody. I wanted to figure out the dern TV so I could have some more Brazilian video fun.

Ahh, yes. The FREE long distance. It became my three companions’ major obsession getting it to work. They kept talking in carrier-ese, and saying stuff about Seattle that I didn’t understand. Jean talked to a couple of people, Sylvia first, and I believe it was fixed in a couple of days. Who knows? I didn’t want to call anybody. I wanted to figure out the dern TV so I could have some more Brazilian video fun.

The night panorama was breathtaking, and had a very calming effect.

But there was the McDonald’s sign in the bottom left corner. The only thing that could serve to yank me back to enough familiar reality to short circuit the scene temporarily. Corporate sponsorship logos are like pimples on a pretty face. That’s pretty dangerous talk for an advertising guy.

Two other very, very important things happened this night.

Two other very, very important things happened this night.

• I learned how very stupid I was for not having taken acidophilus, like our pal Jim Klopman, the world traveler and bon vivant, had told us to do. Robo had his with him, of course, and that evening I began to take it. Even before our Queen Pizza arrived in its nifty round cardboard box.

• Robo told me that the coffee in Salvador was made with the sweet waters of the tap! I may should have watched that.

To top that off, the acidophilus seemed to put me on the road to a miracle cure, and I began to feel better. Surely the placebo effect, but better nevertheless. The few slices of the Queen Pizza I had were delicious. If we ordered it again, given my rate of improvement, we’d have to order something substantially bigger.

Then we figured out the TV.

I could sleep in peace. We had no firm plans for the next day except for getting our Carnaval tickets. We thought maybe Marcelo could kinda show us around a little bit, then we could come back and rest, go out to dinner in Niterói, then go to Carnaval around 11:00.

Why the HELL was Jean setting that stupid Blackberry?

Because Maria was going to have breakfast for us at 9:00, the time we kind of landed on. Nobody wanted to miss THAT.